By Anika Priyaranjan

Illustration by Keo Morakod Ung

The global financial crisis of 2008 shook economies worldwide, pushing governments and financial institutions into a frenzy to stabilise markets and prevent a total collapse. Amidst the chaos, an unexpected player emerged: the drug trade. Despite its illicit nature and societal repercussions, the influx of drug money may have paradoxically helped buffer the impact of the recession.

The failure of major financial institutions and bursting of the housing bubble triggered widespread economic downturns, including plummeting stock markets, rising unemployment rates, and housing market collapses. The recession caused economic activity to slow to a crawl, with both businesses and governments becoming reluctant to spend or invest, exacerbating the liquidity crisis faced by banks.

In contrast, illegal or “black” capital, primarily sourced from activities like drug trafficking, is considered one of the few truly “liquid” forms of capital worldwide. Unlike many legal industries, the drug trade displayed resilience during the recession, with demand for illicit substances often remaining stable or even escalating during times of hardship. Drug trafficking networks adeptly adjusted to shifting economic landscapes, employing diverse smuggling routes and strategies to sustain their operations.

It is also argued that prohibition inadvertently sustains the trade. According to a 2009 UNODC report, the drug sector is estimated to be the largest among illegal industries. In fact, revenue from the drug trade alone may constitute as much as 1% of total global GDP – an estimated $321 billion was spent on drugs in 2003, compared a total GDP of around $38.7 trillion – indicating that 0.83% of world GDP was generated from illicit drug trade.

Antonio Maria Costa, the former head of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, posited that drug money played a pivotal role in rescuing economies. He asserted that proceeds from illegal activities, including drugs, saved banks from the risk of collapse by injecting much-needed liquidity. Without this influx of capital, the crisis could have precipitated a global banking collapse.

According to Costa, the majority of the $352 billion of drug profits was absorbed into the economic system. “The money from drugs was the only liquid investment capital. In the second half of 2008, liquidity was the banking system’s main problem and hence liquid capital became an important factor,” he explained.

However, while it’s possible that some desperate banks may have turned a blind eye to the illegal nature of such funds for survival, crediting the prevention of a financial collapse solely to drug money is a contentious claim. This scepticism was emphasised by a British Bankers’ Association spokesman, who stated: “We have not been party to any regulatory dialogue that would support a theory of this kind. There was clearly a lack of liquidity in the system and to a large degree this was filled by the intervention of central banks and governments around the world.”

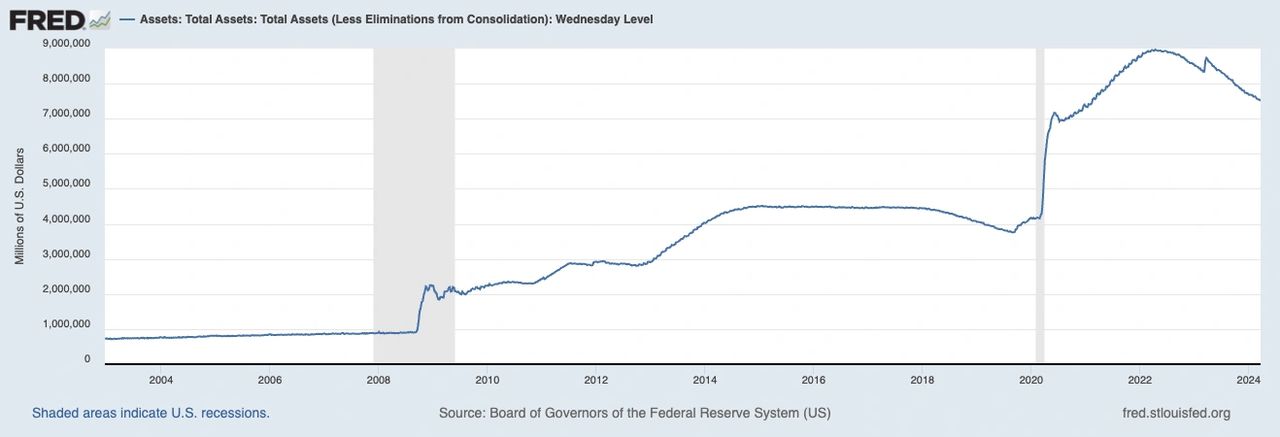

Indeed, in mid-2008, the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet underwent a significant expansion. Between September and November, the Fed increased its total assets by USD 1.3 trillion, dwarfing the $352 billion attributed to drug money. This surge was primarily driven by government and central bank actions, including stimulus packages and quantitative easing, aimed at reducing interest rates, stimulating spending, and shoring up the financial system.

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WALCL

By the close of 2008, the central bank had extended over $1 trillion in loans to banks in a bid to alleviate the liquidity crunch. In 2009, the US government initiated substantial purchases of mortgage-backed securities, including those deemed toxic at the time, aiming to mitigate the risk on banks’ balance sheets. These actions successfully revitalised interbank lending crucial for daily operations. Additionally, initiatives such as TARP, TALF, and various legislative measures provided extensive support to individual banks and the overall financial system, amounting to trillions of dollars and significantly overshadowing the comparatively minor role of $352 billion in drug money.

Although Costa’s observations regarding the impact of drug money during the crisis contain some validity, they fail to comprehensively grasp the multifaceted array of factors and interventions that were pivotal in averting financial collapse. Reflecting on the causes and remedies of the crisis underscores the imperative of addressing systemic vulnerabilities and implementing robust regulatory frameworks to forestall future economic turmoil.