By Manav Khindri

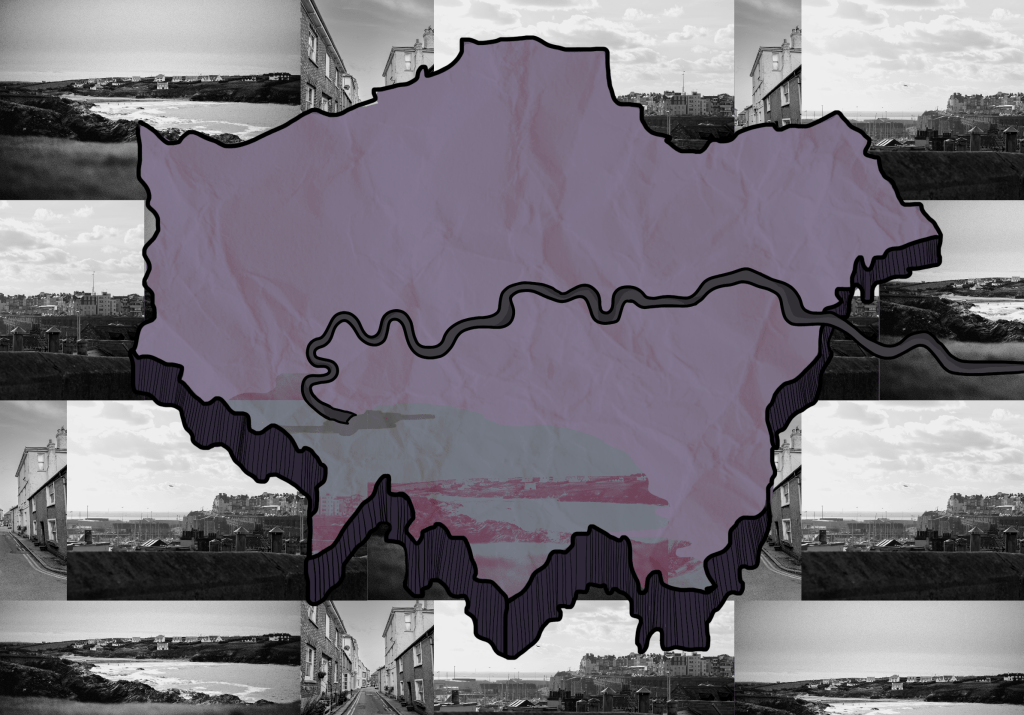

Illustration by Keo Morakod Ung

It is no surprise that London is the financial, cultural and political capital of the UK. With London and the South East responsible for almost 40% of the country’s GDP, and London making up comfortably more than half of it by itself, the English capital sits head and shoulders above most cities within the British Isles. But perhaps the extent of the concentration of power, wealth and importance should come as a surprise. Take Germany, for example; as the biggest economy in the EU, its financial hub, also the largest in mainland Europe, is situated in Frankfurt. Yet many would recognise Berlin not only as the political centre, being the capital, but the cultural hub of the country. The same is true across the pond in the United States, and all over the world. Since the 1970s, London has exploded in both wealth and global importance. But this has come at the expense of other regions, mainly in the North and the South West, ultimately resulting in the so-called ‘death’ of the British town, and the country’s ever-growing London-centrism.

The ‘death’ of the seaside town is a sad, but very real, phenomenon in this country. Due mainly to the advent of cheap international travel and poor mismanagement thereafter (seaside towns pivoted heavily to the working class market after crisis hit, despite this demographic being most likely to want to exploit cheap air travel, resulting in a complete collapse in footfall), many of the UK’s thriving tourist spots, such as Blackpool, Clacton and Hastings, have suffered a painful demise. The knock-on effects on local economies have been dire; towns and villages are getting older (the old age dependency ratio has risen to a stark 36 in 100 people, roughly treble Central London’s 12.7% and comfortably more than the UK mean of 30%). Education is undoubtedly trending downwards in these regions. Indeed, Blackpool ranks very highly for the proportion of inhabitants without a qualification, a whopping 18%. The effect of mass migration out of such regions and towards big cities has been twofold; local towns lack the resources and workforce for meaningful growth, and those who are educated are inclined to move, further widening the gap between the big cities and the rest of the country.

One particular example that encapsulates the cruelly ironic inequality gap in the UK is Cornwall. Although one of the few remaining successful seaside holiday destinations in the country, Cornwall’s seasonal economy means there remains a high level of deprivation and low wages, around a fifth lower than the national average. Yet, curiously, houses in St. Ives fetch in excess of £500,000, 78% more expensive than the national average. Much of this owes to the 13,140 houses in Cornwall classed as second homes, the highest of any county. It is therefore baffling how a deprived area can be given any chance at regeneration if even its locals are priced out by the super-rich, who spend merely weeks out of the year in the region. Although the demise of UK towns cannot exclusively be blamed on London-centricity, this feature of the British economy has made a big contribution to the problem. The contribution of unlived, or rental (think Airbnb) properties to skyrocketing house prices without adding much value to the local economy severely jeopardises local authorities’ ability to reinvent themselves, or attract the talent required in order to reinvent themselves. Without the existence of rival cities, at least not in the South, power, importance and wealth is indubitably concentrated in the capital.

How do the English population feel about this? As reported by Dr Jack Brown of King’s College London, there is a link between how far away places are from London and their connection to it. Regardless of their size, English towns’ and cities’ affinity for or pride in the capital seems to dwindle as geographical distance increases. Despite many of the far-flung regions of the country being net receivers of funding from London, public sentiment seems to indicate a feeling of neglect and disinterest in the rest of the nation. By virtue of London being the administrative hub, there is the widespread belief among local authorities that national decision-makers are subliminally skewed towards the capital’s interests.

London’s isolatedness has only been exacerbated by multiple policy failures. The decision to scrap the northern leg of HS2 by then-PM Rishi Sunak in 2023 has meant that the prospect of increased connectivity between the big northern cities and London has been lost. Even without its catastrophic expense to the taxpayer, the entire HS2 project itself has been deemed by many as simply an opportunity to attract more people into London and consolidate London’s dominance, rather than a plan to boost other parts of the country. Moreover, the previous Conservative government’s ‘levelling up’ scheme, aimed at boosting funding directly to local councils to reduce geographical imbalances, has come under immense criticism. Having been labelled as ‘arbitrary’ and endorsing a ‘begging bowl’ culture, the policy has only served to exacerbate the disconnect between local councils and the capital.

Unfortunately, there is no simple fix to this problem. In the case of the once-powerful seaside towns, it is perhaps just a sad reality of the evolution of international travel. But the fact that people in these towns are being driven out of their towns and given no real chance at regeneration by second-homeowners hailing from the wealthier regions of the country only widens the gap and hinders development. One solution endorsed by Dr Brown is an increase in devolution; centralised government has not proved itself to be skilled in addressing these problems, so local leadership should be trusted to do the job. But the likelihood of central decision-makers being willing to cede power is minimal. Regardless of who is in charge, it is clear that infrastructure policy aimed at connecting northern hubs with London and incentivising industry to move out of London and into places like Manchester is very important. Indeed, the rising cost of living and operations in London in the past few years has begun the process of moving companies to other regions of the UK, but the prevailing importance and perceived favouritism of London within England will only serve to deepen the country’s inequality problem. In addition to all the associated economic problems, it raises the possibility of political instability; where dissatisfaction and inequality is allowed to grow, populist and radical politics can become widespread. As a result, it is definitely in the UK’s interest to tackle its London centricity.

The images pictured do not belong to UCL Rethinking Economics and are courtesy of:

Barry Duncan via Unsplash Free Licensing, “grayscale photography of houses besides river”, published on April 15, 2015, available at https://unsplash.com/photos/grayscale-photography-of-houses-beside-river-d_JvLe9Qvdo

Benjamin Elliot via Unsplash Free Licensing, “a street with buildings on both sides: A street in Marazion, Cornwall”, published on August 4, 2022, available at https://unsplash.com/photos/a-street-with-buildings-on-both-sides-nGuS9ECI6yo

Yeka.uk via Unsplash Free Licensing, “a city skyline with a cloudy sky: Ramsgate, Kent, United Kingdom”, published on April 22, 2022, available at https://unsplash.com/photos/a-city-skyline-with-a-cloudy-sky-6rmtfZZJhdQ