By Anika Priyaranjan

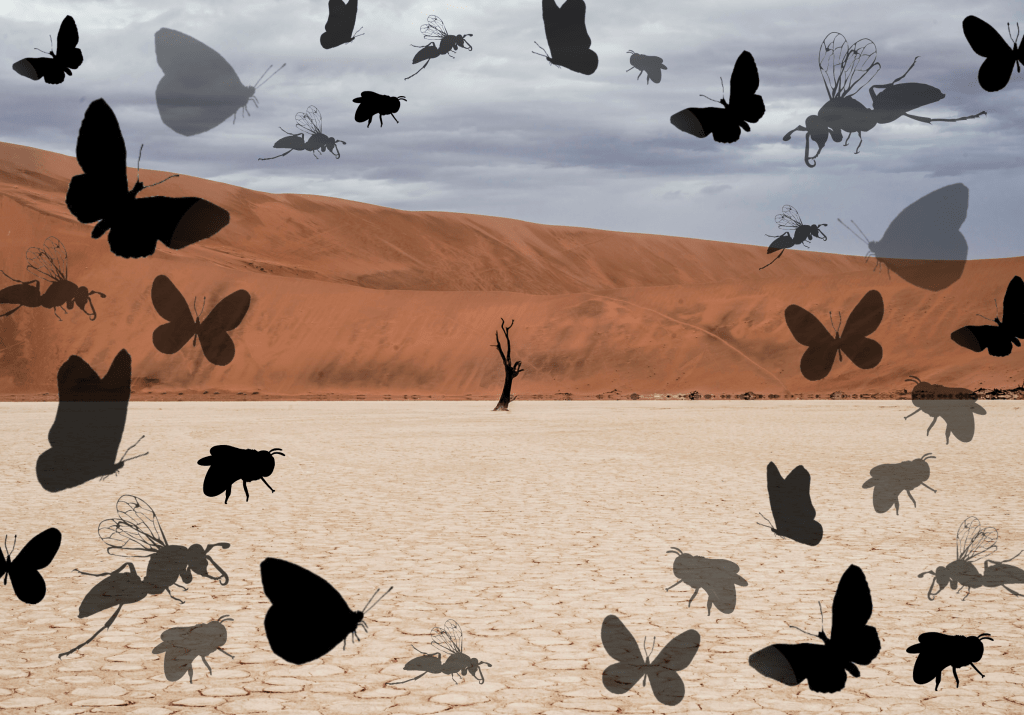

Illustration by Keo Morakod Ung

Imagine you’re at a lavish buffet, overflowing with every dish you could possibly desire. But as you reach for your favourite delicacy, the chef suddenly swoops in and starts removing trays—one by one—until the spread looks more like a sad snack bar than a feast. That, in a nutshell, is what biodiversity loss is doing to our planet. The bill for this dwindling banquet is astronomical, and we’re all footing it.

Biodiversity isn’t just about saving pandas or protecting rainforests—although, who doesn’t love a good panda? It’s the bedrock of our global economy, quietly fueling everything from the food we eat to the medicines we depend on. But as species vanish and ecosystems crumble, the economic consequences are becoming impossible to ignore. So, what happens when we keep pulling species off the plate? It’s going to cost us—big time.

In a strongly worded opening address, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres asserted that “humanity has become a weapon of mass extinction.” The World Economic Forum’s New Nature Economy Report II, also warned about the risks we are creating by destroying nature, stating that “$44 trillion of economic value generation – over half the world’s total GDP – is potentially at risk as a result of the dependence of business on nature and its services”. Five primary pressures—land-use and sea-use change, direct overexploitation of natural resources, climate change, pollution, and the spread of invasive species—are causing steep biodiversity loss. Already, the decline in ecosystem functionality costs the global economy more than $5 trillion a year in the form of lost natural services.

An example of how biodiversity loss can lead to the degradation of services is the decline of the pollinator species like bees and butterflies directly impacts agriculture. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that pollinators contribute to the production of 75% of the world’s food crops. The economic value of these services is estimated to be between $235 billion and $577 billion annually. As climate change exacerbates the decline of pollinators, the resulting loss in agricultural productivity could drive up food prices, reduce food security, and increase the economic burden on farmers and consumers alike. Moreover, the loss of species that contribute to regulating services, such as forests that sequester carbon or wetlands that filter water, can have cascading economic impacts by intensifying the effects of climate change by reducing the planet’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide. The economic costs associated with these events have been consistently rising.

Agriculture is one of the most direct beneficiaries of biodiversity. Healthy ecosystems ensure fertile soils, pollination, and water regulation, all of which are essential for crop production. As climate change alters habitats, many species that provide essential services to agriculture are at risk. For example, the extinction of natural predators due to changing climate conditions can lead to an increase in crop pests, necessitating greater use of chemical pesticides. This not only increases costs for farmers but also has long-term detrimental effects on soil health and water quality. Additionally, the loss of genetic diversity in crops and livestock makes agriculture more vulnerable to diseases and pests. Genetic diversity is crucial for breeding resilient crops that can withstand extreme weather conditions, such as droughts or floods, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change. Without this diversity, the agriculture sector faces greater risks of crop failures, which could have catastrophic economic consequences globally.

The pharmaceutical industry relies heavily on biodiversity, as many medicines are derived from natural compounds found in plants, animals, and microorganisms. With the ongoing loss of species due to climate change, the potential for discovering new drugs is diminishing. Many of today’s most effective drugs, including treatments for cancer, heart disease, and pain management, have their origins in natural compounds. The rosy periwinkle, a plant native to Madagascar, led to the development of drugs that have dramatically increased survival rates for certain cancers. Similarly, the bark of the Pacific yew tree was used to create paclitaxel, a chemotherapy drug. As species disappear, the opportunity to discover similar life-saving treatments diminishes, potentially leading to billions of dollars in lost economic value and missed medical advancements. The extinction of species also disrupts ecosystems that may harbour yet-undiscovered medicinal resources. The rainforests, often referred to as the “pharmacy of the world,” are particularly rich in biodiversity, but they are also among the most vulnerable to climate change. The loss of these ecosystems represents not only a significant economic cost but also a health cost to society.

Despite the clear economic implications, assigning a monetary value to biodiversity is fraught with challenges. Unlike tangible goods, biodiversity and ecosystem services are often public goods—non-excludable and non-rivalrous—making them difficult to price. Moreover, many of the benefits provided by biodiversity, such as cultural and spiritual values, are intangible and resist quantification. Economic valuation methods, such as contingent valuation (willingness to pay) and ecosystem service valuation, attempt to estimate the monetary value of biodiversity. However, these methods are often criticised for underestimating the true value of biodiversity due to methodological limitations and the difficulty of capturing the complex interdependencies within ecosystems. Furthermore, the value of biodiversity is often realised only after it is lost, at which point it may be too late to reverse the damage. This makes proactive conservation economically challenging, as the immediate costs of conservation are more tangible than the future benefits of avoided losses.

Given the economic risks associated with climate-induced species extinction, there is an urgent need for robust policy responses. These policies should aim to internalise the value of biodiversity into economic decision-making, incentivize conservation, and mitigate the impacts of climate change. One solution may be the implementation of biodiversity offsets, where developers are required to compensate for the loss of biodiversity caused by their activities by investing in conservation elsewhere. International cooperation is also critical, as biodiversity loss and climate change are global challenges that transcend national borders. Strengthening international agreements, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Paris Agreement, such as by making them legally binding, can help to coordinate efforts to protect biodiversity and combat climate change. Current steps taken like increasing education on climate change and creating carbon credit markets are good, but not sufficient. By recognizing the true value of biodiversity, society can begin to take the necessary steps to protect it, ensuring that the economic and ecological foundations of our world remain intact.

The economics of climate-induced species extinction presents a complex and urgent challenge. As biodiversity declines, the ecosystem services that underpin our economy are at risk, with potentially devastating consequences for agriculture, pharmaceuticals, and global well-being. While assigning economic value to biodiversity is difficult, it is essential for informing policy and driving conservation efforts. In the end, the cost of doing nothing is far greater than the cost of action.

Background photo courtesy of:

Ivars Krutainis of “Brown tree on dried ground at daytime in desert”, Deadvlei Hiking Trail, Namibia, published on November 29 2015, available via Unsplash Free Photo Licensing