By Manav Khindri

Illustration by Keo Morakod Ung

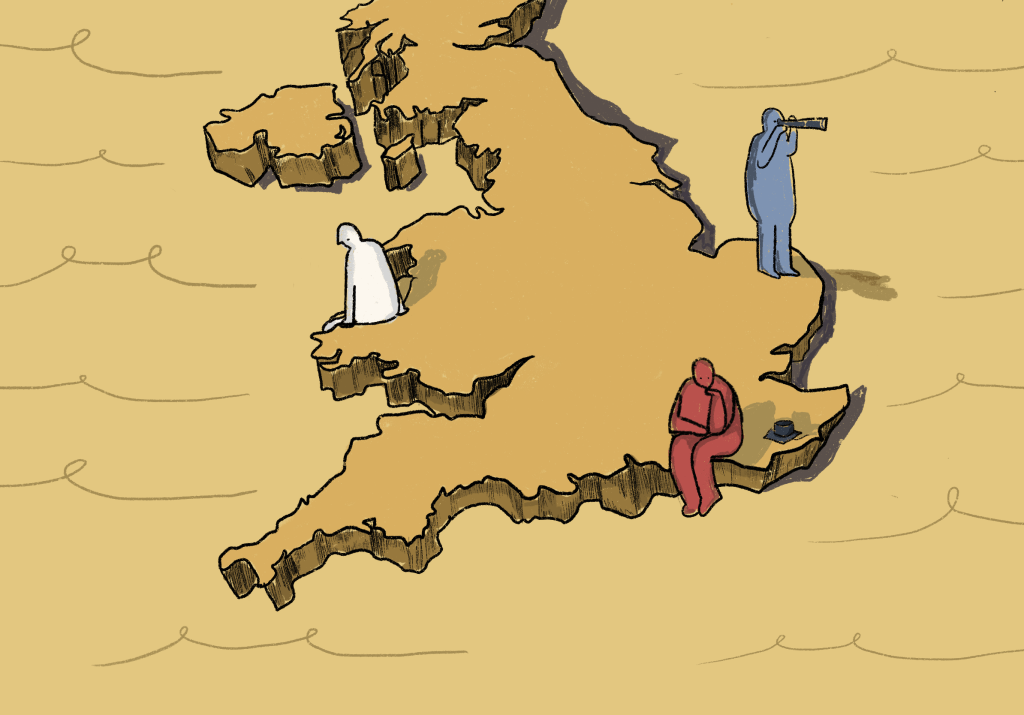

To the approximately 900,000 young adults who are set to receive their undergraduate degrees in the summer, and the many million who have come before them in recent years, the harsh realities of the graduate job market in the United Kingdom in 2024 are clear to see. Many young people find it hard to land a graduate role, often taking up to two years before they are able to break into the very positions that their university qualification was meant to have facilitated. Not only do many graduates face long waits and scarce vacancies, but their prospective salaries pale in significance when compared to the other large economies of the world – while a typical recent graduate from even the most elite of UK universities, Oxford, can expect to earn approximately £35,000 a year, those graduating from Ivy League universities in the United States can expect to earn an annual salary upwards of $85,000. As UK graduates grapple with a dwindling ‘graduate premium’ over their lifetime earnings, an oversaturated job market and a rise in payments on their student loans leading them to question the value of a university education, it begs the question: what has led us to this point, and why does this crisis seem to disproportionately affect the British job market?

It is no secret that the UK job market is still feeling the squeeze of the Covid-19 pandemic, both directly and indirectly. Many graduates who chose to take gap years, postpone their studies or undertake postgraduate qualifications during the early 2020s add to the ever-widening pool of applicants jostling for position in the race for an ever-dwindling number of entry-level roles. It is, indeed, also true that the general trend over the past 70 years of widening access to university via the expansion of tertiary education has contributed to this over-saturation: in 1950, only 3.4% of 17-30 year olds attended university in the UK, rising to 53% in 2019. But this simple explanation, while helpful at first, does not paint the full picture. Even today, the UK and US have a similar proportion of the population who are graduates, yet their prospects are vastly different: from 2007-2021, the real value of income for a US millennial graduate rose by 15%, whereas it fell by 9% in the UK. The explanation to this problem lies in the productivity of both economies, and, in the case of the UK’s shortcomings, the inability to adapt to the economy’s skills demands.

Despite the UK’s prominence in some traditional industries, such as finance – London remains second only to New York in the Global Financial Centres Index, holding a significant advantage in some of the more advanced, sophisticated forms of finance – it remains absent from the forefront of the modern technology industry. Not one of the top 10 tech companies by market capitalisation is European, let alone British. Across the pond, the United States prides itself on its diverse tech startup culture, where bold risk-taking and learning from failure underpin its position as the market leader in a huge industry. Some of the most lucrative STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) degrees in the United States offer the chance to break into these adaptive industries in the high-skilled sector.

By contrast, the United Kingdom has long struggled to meet the needs of its economy with its existing structure. More than 80% of the UK economy is comprised of the finance, entertainment and education industries. Somewhat ironically, the level of education seems to fail to address areas of key shortages – on the government’s Shortage Occupation List, jobs in science, technology, nursing and medicine seem especially undersupplied – perhaps, due to the UK education system’s unusually early levels of specialisation at the age of 16, many are put off undertaking some of the highly specialised vocational routes, while these options are accessible aged 20/21 to pursue in universities abroad. Combined with the UK’s chronic underproductivity – around 16% less than both Germany and the USA – wages are being kept lower than abroad in these undersubscribed jobs amid high costs of living, meaning that elite talent is increasingly looking elsewhere.

As such, the UK’s uniquely puzzling graduate crisis seems to be just that: unique. With mismatched skills, undesirable salaries versus the rest of the world and a larger-than-ever pool of graduates vying for a role, it does not seem, somewhat ominously, like a problem with a quick fix.