By Albertina Robinson-Welsh

Illustration by Keo Morakod Ung

When the world’s population surpassed 8 billion on the 15thof November 2022, many people raised concerns about the impact of the Earth’s growing population on the current climate crisis – or, quite simply, overpopulation.

These fears are nothing new, however. In fact, this concept was first introduced by Thomas Malthus in his Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), who claimed that the ‘power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man’, which raised awareness on the impact of overpopulation on resource depletion. More recently, this issue has also been explored by the American ecologist Paul Ehrlich in his book ‘The Population Bomb’ (1968), which fuelled growing fears that humanity was running out of space, whilst also claiming that ‘hundreds of millions of people were going to starve’.

In theory, it makes sense why an increase in the world’s population accelerates the rate of climate change. More people inevitably create more stress on resources such as food, water and fossil fuels. This adds more anthropogenic emissions to our atmosphere, contributing to the enhanced greenhouse effect and thus bringing Earth closer to its tipping point. In fact, it was estimated that explosive population growth to 8 billion would see a 19 billion-tonne CO2 spike. In addition, countries such as China have even implemented policies in the past such as the one-child policy to curb population growth in an effort to reduce resource strain.

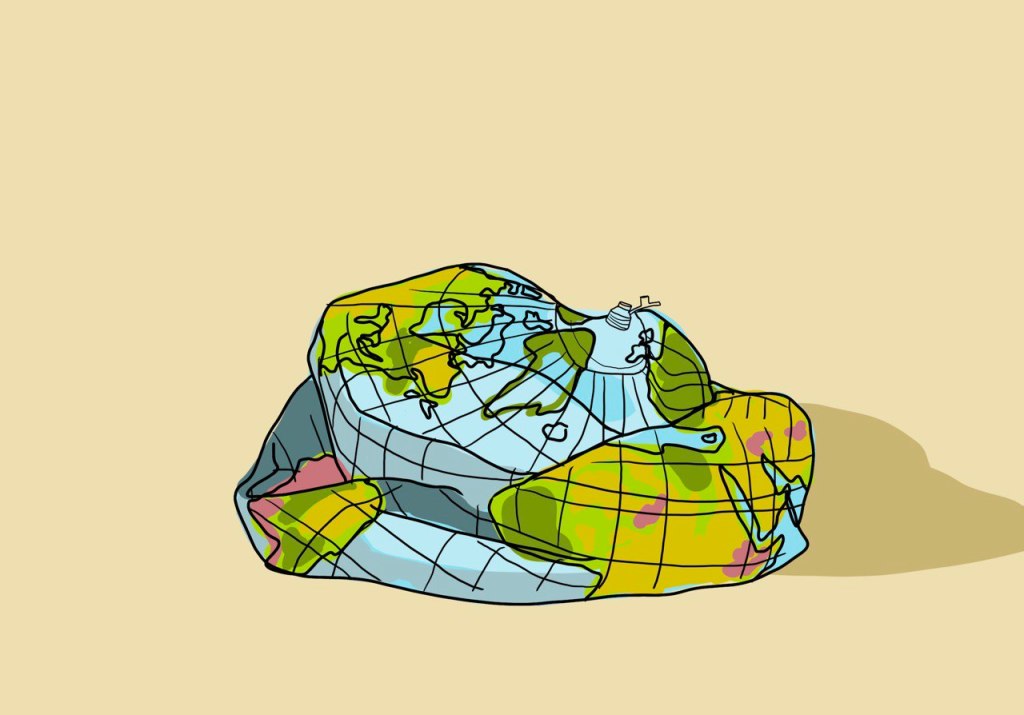

However, what many people fail to consider is that, on a global scale, population growth is slowing; we are certainly expected to reach peak population by the end of the century. What should be more alarming instead are the staggering levels of consumption, particularly in developed countries, that are pumping vast amounts of CO2 emissions into our atmosphere daily. It takes just under two weeks for the average person in the UK to emit as much as the average Malian does in a year, and only four days for the average Australian. Especially when one considers that most population growth is only happening in LIDCs, which tend to have the lowest consumption rates per capita, it becomes evidently clear that overconsumption, rather than overpopulation, is the main underlying cause of climate change.

In 1972, Earth Overshoot Day occurred on December 27th, the date when humanity has exhausted nature’s budget for the year. This means that back in 1972, we were consuming a sustainable amount of Earth’s resources. Yet in 2024, it fell on August 1st as a result of worldwide resource extraction quadrupling over the same period of time. Much of this can be attributed to rising incomes in the developed world and the increase in popularity of the so-called ‘American lifestyle’. Meat consumption, for example, has almost doubled per person since 1961, releasing methane (a far more potent greenhouse gas than CO2) into the atmosphere. In addition, technological advances have also increased production capacity, leading to the rise in damaging trends such as fast fashion, which is the second biggest consumer of water and responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions. Similarly, the rise of social media has led to increased marketing and has acted as a catalyst for feelings of inadequacy, nudging consumers to purchase items they really do not need. This has greatly contributed towards landfill waste and has led to the creation of trash islands such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. As a result, high-income countries now consume six times more resources than low-income countries, making them the leading contributors towards climate change despite having the lowest rates of population growth globally.

Many people tend to also dismiss the benefits of having a large population. More people increase both the quality and quantity of human capital, which allows for greater advances in technology. For example, the Green Revolution saw the increased availability of higher-yielding seeds and chemical fertilisers to the Global South. This movement was estimated to have saved 1 billion people from starvation, debunking the theories of both Malthus and Ehrlich, who claimed that exponential levels of population growth beyond the earth’s ‘carrying capacity’ would lead to widespread famine. In reality, there is no such thing as a carrying capacity. Improved efficiency due to technological advances has allowed us to get more people out of the same amount of planet. Looking ahead, greater human capital can allow us to increase the usage of sustainable technologies like Carbon Capture Storage (CCS) or precision agriculture, which can hopefully help to mitigate the devastating impacts of climate change in the future.

Whether one believes there are 8 billion too many or too few in our world, it is undeniable that the global rich’s consumption is unsustainable and detrimental to our planet. Therefore, addressing overconsumption, above overpopulation, is what is most vital for tackling climate change.