By Kashvi Singh

Illustration by Keo Morakod Ung

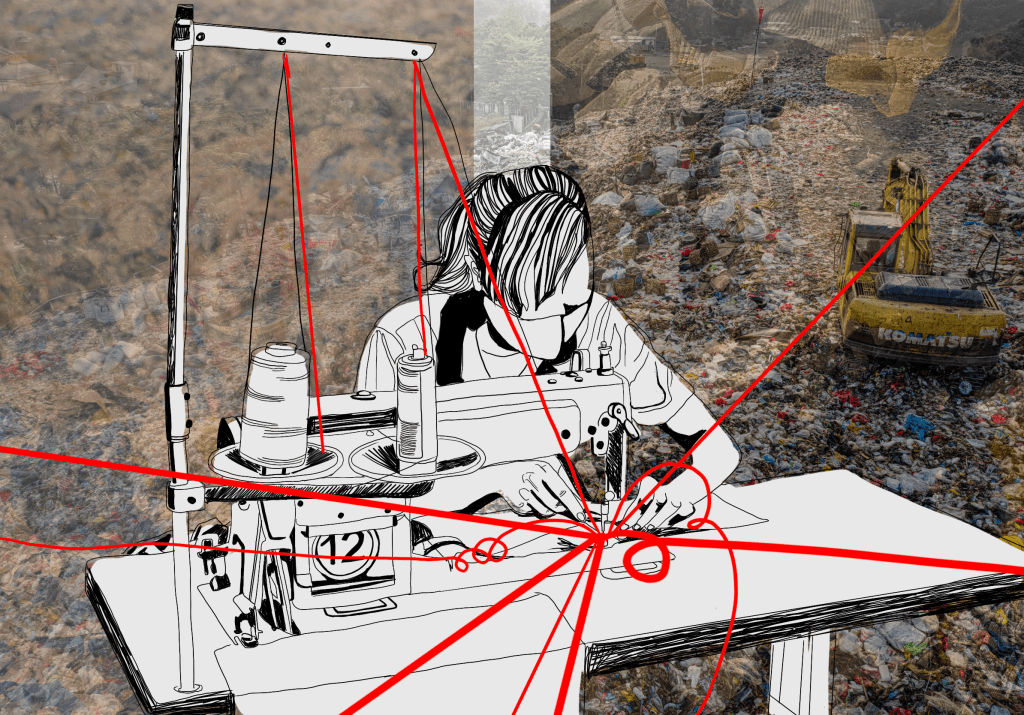

We’ve all encountered headlines about the human and environmental costs of the fast fashion industry, a behemoth that churns out cheap, trendy clothes at alarming rates. The environmental damage is staggering—from the vast quantities of water used to produce textiles to the toxic dyes and untreated waste polluting rivers in production hubs like Bangladesh and China. The industry consumes approximately 93 billion cubic meters of water annually, enough to meet the needs of 5 million people. At the same time, wastewater from synthetic fabric production releases harmful pollutants like lead, arsenic, and benzene into water sources, compounding the crisis.

Fast fashion also plays a significant role in global carbon emissions. The fashion industry is responsible for around 10% of total global carbon emissions—more than international flights and maritime shipping combined. This high carbon footprint is driven by the energy-intensive production processes, especially the manufacture of synthetic fibers, which rely on fossil fuels, and the long, complex supply chains that transport materials and finished goods globally.

Yet, the environmental crisis generated by the industry doesn’t end at production and merchandise. Fast fashion also contributes massively to textile waste, with millions of tons of discarded clothing ending up in landfills each year. In places like Chile’s Atacama Desert, mountains of unsold or discarded clothes are dumped, creating toxic waste that will take centuries to decompose.

The human costs are equally depressing. Garment workers, primarily in developing countries, are subjected to poor working conditions, long hours of up to 75-hour weeks, and extremely low wages to meet the relentless demand for cheap, rapidly produced clothing. In Bangladesh, even after a wage increase in 2023, garment workers earn only $113 per month—far below the $210 living wage needed to cover basic expenses. Tragic incidents, like the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013, have underscored the dangerous conditions that workers face as brands prioritise speed and cost-cutting over safety.

In addition to the ethical and environmental costs, consumers bear a personal cost as we march deeper into the fast fashion wave. The decline in clothing quality—from flimsy fabrics to poor tailoring—has been extensively analysed by experts. Many fast fashion garments are designed to be worn just a few times before falling apart, meaning we often end up buying more to replace them, fuelling the cycle of overconsumption. As materials become cheaper and synthetic fibres more common, our wardrobes are filled with lower-quality, less durable clothes.

Despite widespread awareness of these issues, we continue to fuel this industry with our purchases. Shein, a dominant force in the apparel industry, is estimated to generate over $30 billion in annual revenue, with brands like Temu, H&M, and Zara operating on a similarly massive scale. This constant cycle of overproduction and overconsumption isn’t just a business case study—it’s a symptom of a larger issue that demands our attention. The relationship between fast fashion brands and their consumers lies at the heart of this cycle, and understanding this interaction is key to addressing the significant social and environmental challenges the industry creates.

Business model: How Brands Keep Us Coming Back for More

Fast fashion brands have perfected the art of keeping consumers on a constant cycle of purchasing, and a large part of this comes down to strategic misinformation and overconsumption. The misinformation machine, as explained by Vox’s Kim Mas, is a well-oiled system that promotes overconsumption through a variety of tactics. While the quantity of clothing we purchase has skyrocketed, the share of income U.S. consumers spend on clothing has halved since the 1980s. This affordability fuels a disposability culture, where clothing is viewed as temporary, and trends change rapidly.

Social media and influencer culture have accelerated this, with platforms like Instagram and TikTok normalising “hauls” that promote mass consumption. The idea that repeating outfits is undesirable feeds the fast fashion cycle, as brands like Shein, H&M, and Zara ensure there’s always something new to buy.

Another key factor in the fast fashion business model is the lack of transparency. Many brands remain secretive about their supply chains, obscuring the exploitative labour practices and environmental degradation that underpin their low prices. This lack of transparency allows them to portray an illusion of ethical responsibility while continuing to operate unsustainably.

However, this cycle didn’t begin with social media or Shein. It’s the result of broader social, legislative, and economic shifts that began in the 90s, including trade liberalisation, globalised supply chains, and corporate lobbying. These factors set the stage for the ultra-fast fashion wave we see today. For more insights into this, check out More Perfect Union’s video “It’s Not Just Shein: Why Are ALL Your Clothes Worse Now?”.

Breaking the Cycle: Stitching a New Future for Fashion

Factors like greenwashing, affordability, and a lack of sustainable options have intensified the internal conflict consumers face—torn between the desire for trendy, affordable clothes and the awareness of their environmental and ethical costs. While it’s difficult to completely avoid fast fashion, we can take steps to slow it down by redefining our relationship with clothing.

Historically, clothing was something to cherish and keep, and we can benefit from returning to that mindset. Instead of chasing trends, investing in quality, long-lasting pieces can reduce waste and bring more value to our wardrobes. Avoiding ultra-fast fashion brands like Shein is a good first step, as some brands offer more sustainable options than others. With time, embracing second-hand shopping and learning basic mending skills can extend the life of our clothes, reducing waste and helping us slow down the unsustainable pace of fast fashion.

Another key step is developing your personal style. Fashion brands profit when consumers constantly follow trends, so building a wardrobe based on your unique style can help reduce impulse buying and take the pressure off always having the latest look.

Becoming an ethical consumer isn’t easy—it’s a process. But at its core, we must recognise that no fashion trend is worth the immense cost to our planet and the people who produce these clothes.

Solidarity networks and worker unions also play a critical role in challenging the fast fashion industry’s exploitative practices. For example, following the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013, which killed over 1,100 garment workers in Bangladesh, global labour movements united to demand better safety standards. These efforts led to the Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a legally binding agreement, aimed at improving working conditions.

On the legislative side, stronger regulations are essential to enforce real change. Governments must crack down on greenwashing by imposing substantial penalties on companies that make false environmental claims. They must ensure stricter regulations on worker health, safety, and fair pay, and mandate transparency in supply chains with environmental and labour disclosures. Only with coordinated action amongst workers, consumers, and policymakers, can we begin to unwind this destructive cycle and push the fashion industry toward a more sustainable future.

Further Reading & Resources

Our Changing Climate. (2022, Aug 26). How We REALLY Stop Fast Fashion [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=04dSAUAoitY